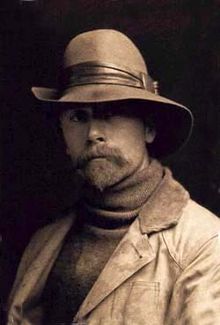

EDWARD SHERIFF CURTIS

“Shadow Catcher” (1868-1952)

Perhaps America’s best-known photographer of Native Americans and the West, Edward S. Curtis spent three decades immersed in the culture of our nation’s indigenous peoples during the early 1900′s .

His ambitious project involved photographing more than eighty tribal groups west of the Mississippi–everyone from the Eskimo (Inuit) in the far north to the Hopi and the Comanche in the southwest to the Ute and Cheyenne and a multitude of others in between.

Curtis was born in 1868 near Whitewater, Wisconsin where he lived until he was six years old. HIs father, a Reverend and Civil War veteran, then moved the family to Minnesota.

Around that time more than 200 battles were being fought between US troops and Native American tribes–from the Dakota Territory down to Mexico. When Edward Curtis was eight years old Sioux and Cheyenne warriors defeated General George Custer and his troops at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Curtis went to school until sixth grade then dropped out. Soon after he became interested in photography and built his first camera. The lens for his camera was brought back from the Civil War by his father. He and his father also shared a love of the outdoors and spent time together camping and canoeing. At seventeen, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, then two years later, when his family moved to Seattle, he became a partner in a photo studio.

Curtis went to school until sixth grade then dropped out. Soon after he became interested in photography and built his first camera. The lens for his camera was brought back from the Civil War by his father. He and his father also shared a love of the outdoors and spent time together camping and canoeing. At seventeen, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, then two years later, when his family moved to Seattle, he became a partner in a photo studio.

His first Native American portrait, created in 1896, was of Princess Angeline, the elderly daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. It wasn’t long after that he launched into his epic project documenting the Native American traditional way of life–their dress, ceremonies, food, clothing, dwellings, burial customs, manners, and daily life.

Though he struggled to gain funding, eventually J.P. Morgan offered him $75,000, to be paid at $15,000 per year for five years, to create his 20-volume series entitled The North American Indian. It would comprise over two thousand photogravure plates and narrative about America’s indigenous, and Curtis feared, vanishing people. Native Americans were considered “savages” by many at the time, forced from their land and stripped of their rights.

Curtis would later write the following foward to Volume I of The North American Indian.

“The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once….”

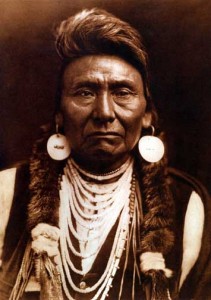

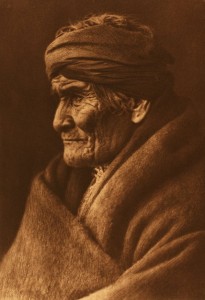

During this ambitious project, Curtis became known by some tribes as the “Shadow Catcher” as he captured the likeness of many important and well-known Indian people of that time, including Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow and others. Not only did he create thousands of images, but he recorded hours of rare ethnographic information, including some 10,000 wax cylinder sound recordings of Indian speech, music, and tribal mythologies.

It took far more than five years to create all twenty volumes, and far more money. Curtis sacrificed much in order to fulfill his dream of documenting America’s indigenous peoples. Not only was he perpetually broke, and continually trying to find financing for the project, but his family life took a beating as well. His wife divorced him after twenty-seven years and his four children grew up essentially with an absent father much of their childhoods.

Curtis’ photographs, while recognized as some of the most important work of its time, have received criticism because they are said to be romanticized versions of Native American culture, and contrived reconstructions rather than true documentation. He was known at times to remove “modern” items from an image to make it more authentic.

Below are images selected from The Library of Congress’s Edward S. Curtis Collection. Some were published in The North American Indian. Others were not.