THEN: BEYOND RANGOON (PART TWO)

APRIL 1989: As you might remember in Part One of this story (see my post on 9/27/11 if you missed it), the last time I hear from Jeffrey is when he’s in Bangkok, on his way to Rangoon to photograph a seemingly innocuous story about daily life in Burma for The Christian Science Monitor.

These are the days before email, iChat, text messaging and the constant stream of news gliding across our televisions and computer screens, so while I’m aware of Burma’s dark history, I’m unaware of Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent arrest or the military crackdown Jeffrey is about to drop himself into. We are completely out of contact for ten days.

Now, if you will, flash forward with me to when Jeffrey arrives home from Burma…

I can tell by Jeffrey’s glassy eyes that he’s exhausted. The kind of exhausted that makes yawning feel like too much effort.

When I ask how his assignment went, all he can say is, “Insane.”

I can’t tell if it’s a good insane or a bad insane. Then he grabs a box of slides out of his carry-on bag. I try to imagine why he would have had his film processed in Asia instead of the lab at home like he always did, but instead of asking, I open the box, grab a loupe and take a look at the slides.

When I see Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s most powerful symbol of hope and freedom, staring back at me instead of water buffaloes and golden temples, I’m stunned.

“How in god’s name did you photograph Aung San Suu Kyi?” I stammer.

“It’s a very long story,” Jeffrey says, exhaling deeply and throwing himself into a chair.

It isn’t until the following evening over dinner and a bottle of wine that Jeffrey finally recounts the details of his trip. Goosebumps rise on my arms as he describes it all.

This is but a tiny portion of what he experienced…

Excerpts from Chapter Three of my book…

Ko Ye’s leathery brown hands grip the steering wheel, slowly navigating the embassy car through the streets of Rangoon. Armed soldiers lining both sides of the road peer inside the windows, and beads of sweat drip down the driver’s temples and neck.

The only sound in the airless car is an unspoken symphony of anxiety created by three pounding hearts, the rumble of the diesel engine, and Ko Ye’s laden sighs.

At the first roadblock, the driver’s eyes flash in the rearview mirror to Jeffrey and Andrew, the two journalists in the back seat, reinforcing the insanity of what they’re doing. Upon order, he slowly rolls down the window; nobody dares breathe.

Jeffrey carefully shifts his knees to make sure his camera bag is covered on the floor below. Andrew looks straight ahead. Angry Burmese words are launched at Ko Ye. The passengers have no idea what’s being said, but somehow the driver’s shaky, high-pitched response convinces the soldier to wave them through.

Nearly a half hour later, after several more chilling roadblocks, they arrive at a compound near Inya Lake. A wall of soldiers surrounds the entrance, and it’s clear that whomever’s inside, is at the will of the AK-47’s outside. The embassy car is the only reason the solid metal gate opens, and as Ko Ye slowly pulls the car forward, Jeffrey and Andrew finally allow themselves to exhale…

______________

…On the veranda of the faded two-story colonial villa, a slender woman wearing a simple flowered blouse and a green traditional longyi sits waiting. Her thick black hair, pinned back with a hibiscus, frames her high cheekbones and delicate oval face.

When Aung San Suu Kyi stands and graciously welcomes them in her perfect Oxford English, Jeffrey takes a moment to center himself, trying to remember how he arrived at this unexpected moment in his photographic career.

When Aung San Suu Kyi stands and graciously welcomes them in her perfect Oxford English, Jeffrey takes a moment to center himself, trying to remember how he arrived at this unexpected moment in his photographic career.

He flashes back to breakfast earlier that morning. His camera bag is sitting in the chair next to him, and he suddenly notices a foreigner watching him. Not sure what to make of it, he half-smiles, then finishes his breakfast, all the while trying to imagine what this guy is about. Before he has a chance to speculate further, he hears an Australian voice say, “You’re a photographer, right?”

Jeffrey cocks his head and looks up out of the corner of his eye, instinctively putting up his defenses.

“Nope…just here on vacation.”

Before Jeffrey has time to ask him who he is or what he’s about, the Aussie interrupts and sits down at the table, throwing his hand out to shake. “I’m Andrew Walsh,” (his name has been changed to protect his identity) he announces, then lowers his voice, “I’m a reporter for The Age in Australia.”

Then he quickly begins telling his story in a hushed tone. “Listen, my country is the only democratic country in the world right now that hasn’t broken diplomatic relations with Burma after Aung San Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest.” He looks around to make sure nobody else is listening.

“I have an opportunity to use the Australian Embassy car to go interview her this afternoon, and I need a photographer. We’ll be going under the auspices of checking on her—sort of a diplomatic mission for the embassy—to make sure she’s all right.”

Jeffrey has a hard time believing the proposition he’s hearing, but Andrew continues, “In exchange for this exclusive opportunity, I just need one photograph of her for my story. Then you’ll have free reign of everything else. We’ll even pay you for licensing the photograph.”

Andrew doesn’t need to sell Jeffrey. Exposing human rights abuses and injustice in the world drives Jeffrey from his belly. Grabbing his camera bag, he asks, “When do we leave?”

___________________

…Inside the heavily treed compound humidity and oppression hang on Andrew and Jeffrey like wet quilts. The stifling air doesn’t budge, but the energy radiating from Aung San Suu Kyi swirls into an electrifying breeze.

While Jeffrey patiently waits for Andrew to interview her, he mentally composes photographs in his head. He’s also swept away by the poise and defiance of this striking 44-year old woman. A wife and mother, and Burma’s most powerful voice for change, she exudes grace while fearlessly trying to lead her party and country in a new direction…

In perfect English, she articulates her hopes and dreams for her country and reveals the reality of its past. “Our party is expected to win the majority of parliament seats during the upcoming election,” she explains, “but the junta is cracking down, afraid to lose its power. You can’t have power without responsibility.”

… Jeffrey, knowing there isn’t much time left before the light disappears, begins photographing. Quickly placing the bright red flag of The National League for Democracy behind her, he shoots frame after frame, capturing the mix of intellect, warmth and defiance in her eyes.

Her chapped lips and the shadows under her eyes reveal the vulnerability of a woman who’s been treated harshly, but also the stoicism of a leader whose fortitude could never be underestimated. Then he captures the family connection and the love of her country as she sits near a large portrait of her father, General Aung San, who negotiated Burma’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1947. As she tells the story of how he was assassinated when she was just two years old, the harsh reality of her country is hammered home even more.

Her chapped lips and the shadows under her eyes reveal the vulnerability of a woman who’s been treated harshly, but also the stoicism of a leader whose fortitude could never be underestimated. Then he captures the family connection and the love of her country as she sits near a large portrait of her father, General Aung San, who negotiated Burma’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1947. As she tells the story of how he was assassinated when she was just two years old, the harsh reality of her country is hammered home even more.

In no time, the light fades and they know they must leave.

As they depart the compound, Aung San Suu Kyi’s last words grip them…“Let the world know.”

______________________________

When Jeffrey finishes telling me this story, then shares other details about the sketchy drive back from her compound, how he duct-taped his undeveloped film to the bottom of his hotel bed to keep it safe, and how he and Andrew also used the embassy car to photograph a demonstration in which dozens of protesters were slaughtered, I count my blessings that he made it home safely.

What resonates most though, are Aung San Suu Kyi’s words, “Let the world know.” Jeffrey and I both know it’s our responsibility to get his images published so people can see what’s happening in Burma.

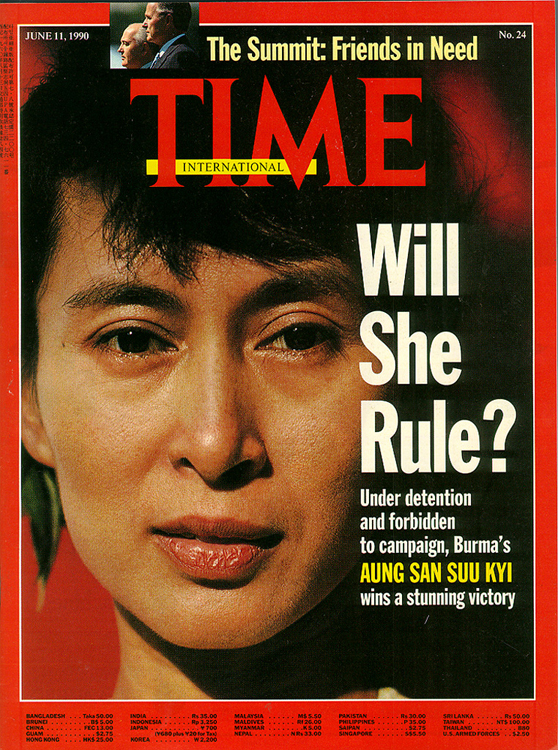

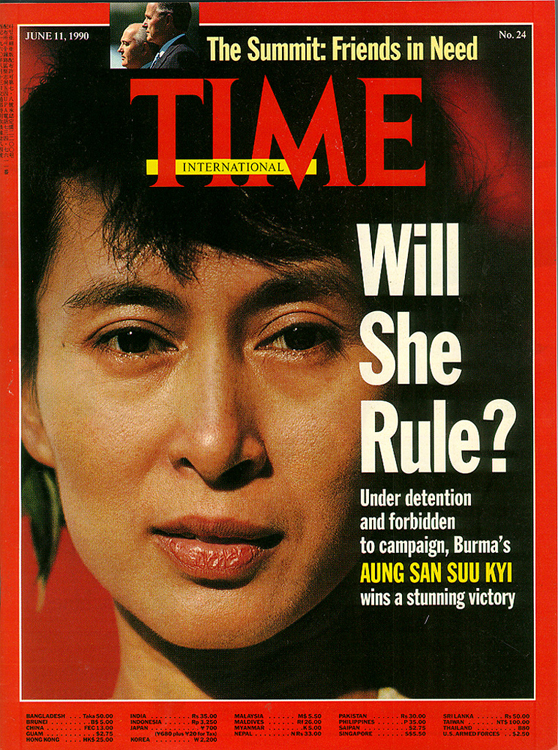

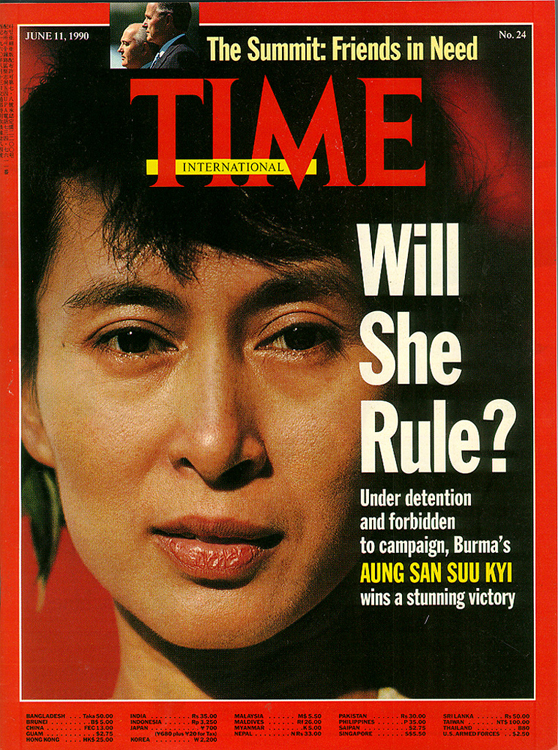

In the coming months and years, that is exactly what we try to do. Not only does The Age publish one of Jeffrey’s photographs, but his portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi become the most published photographs of her ever. One graces the cover of Time Magazine when she wins the Burmese elections, and later when she wins the Nobel Peace Prize. Others are splashed across dozens of magazine covers in Europe, Asia and Latin America, in every kind of publication, large and small.

Her face becomes the light in the midst of Burma’s darkness, a symbol of courage and strength around the world. Like Nelson Mandela and the Dalai Lama, she gives up everything for what she believes in, and its her sacrifice and fortitude that inspire veneration around the world.

Her words are also one of the reasons I’m writing my book…to let the world know.

____________________

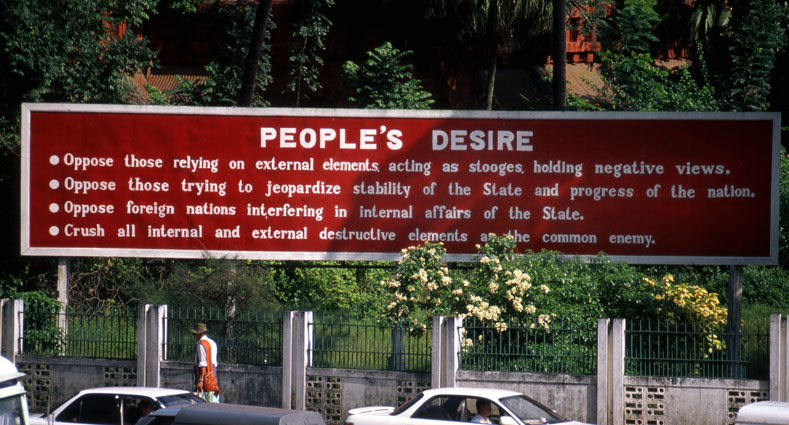

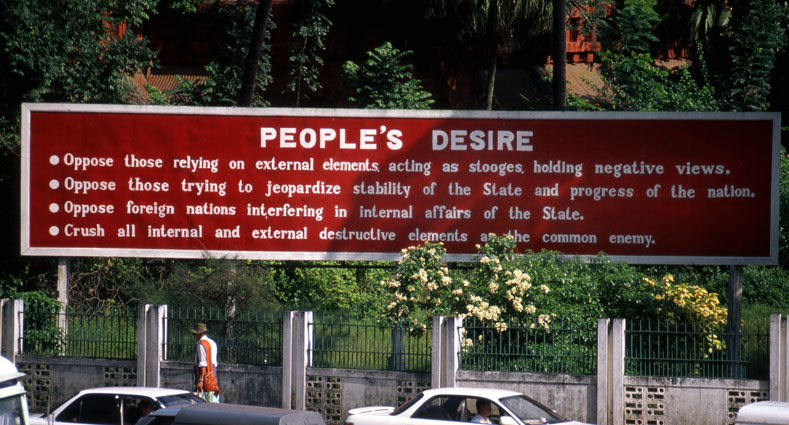

Postscript: In November 2010 Aung San Suu Kyi was finally released, after spending most of the last 21 years in some form of imprisonment. She continues to fight for democracy and freedom for the Burmese people. The billboard below is an example of the challenges she faces. Click on it to view it larger.

Photo of a government propaganda billboard, 1996

SUMMER 1989: Jeffrey arrives home safely from Beijing and I count my blessings that he has avoided harm while photographing the Democracy Movement and its grim aftermath.

SUMMER 1989: Jeffrey arrives home safely from Beijing and I count my blessings that he has avoided harm while photographing the Democracy Movement and its grim aftermath.