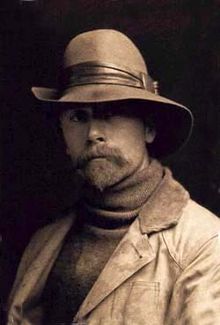

EDWARD SHERIFF CURTIS

“Shadow Catcher” (1868-1952)

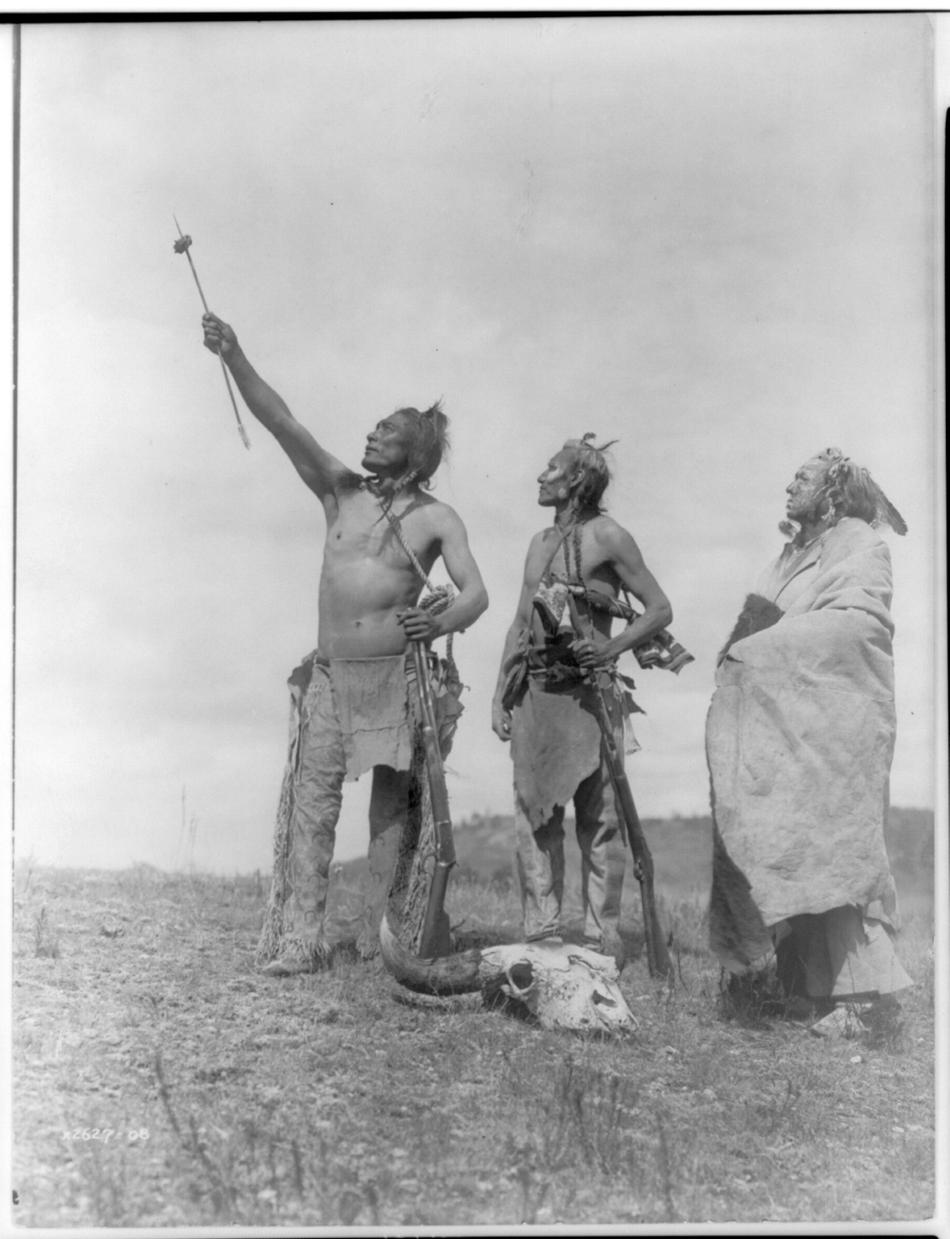

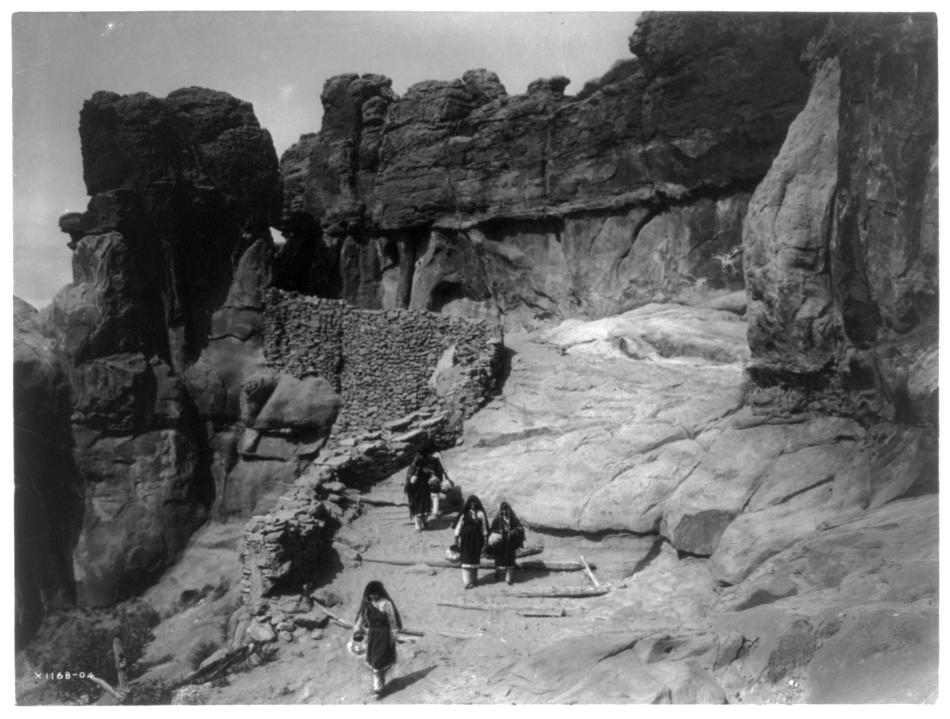

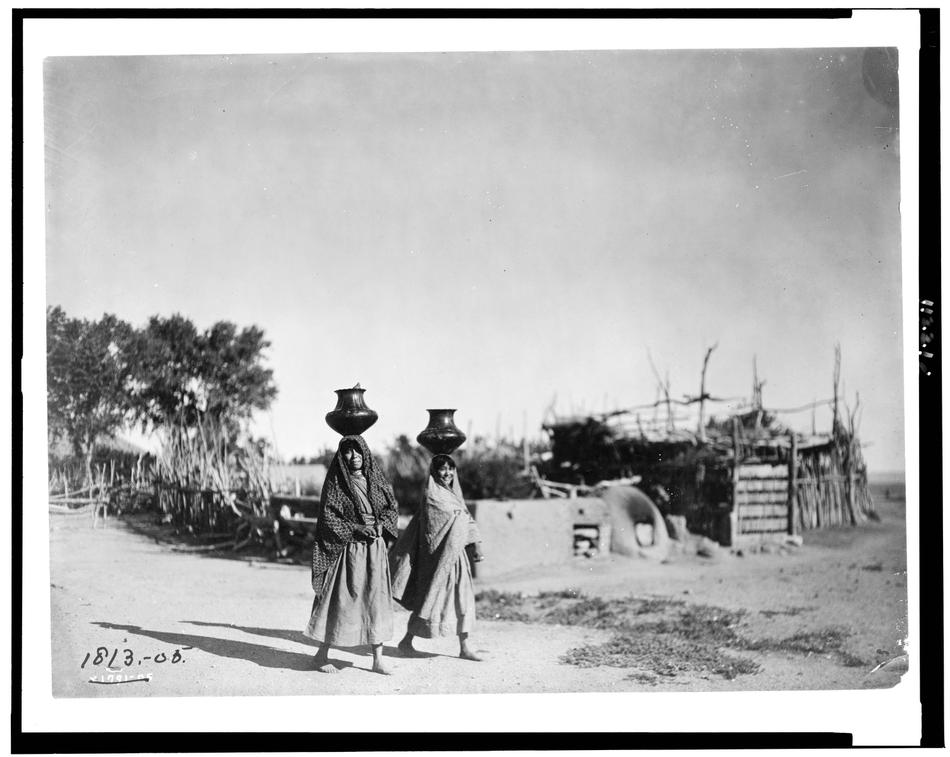

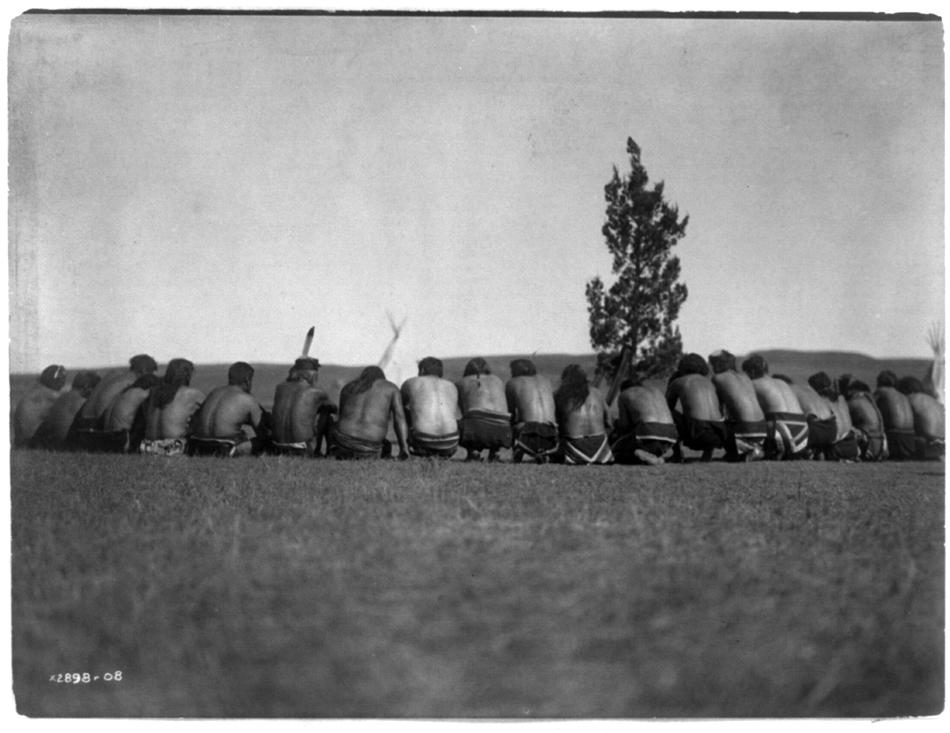

Perhaps America’s best-known photographer of Native Americans and the West, Edward S. Curtis spent three decades immersed in the culture of our nation’s indigenous peoples during the early 1900′s .

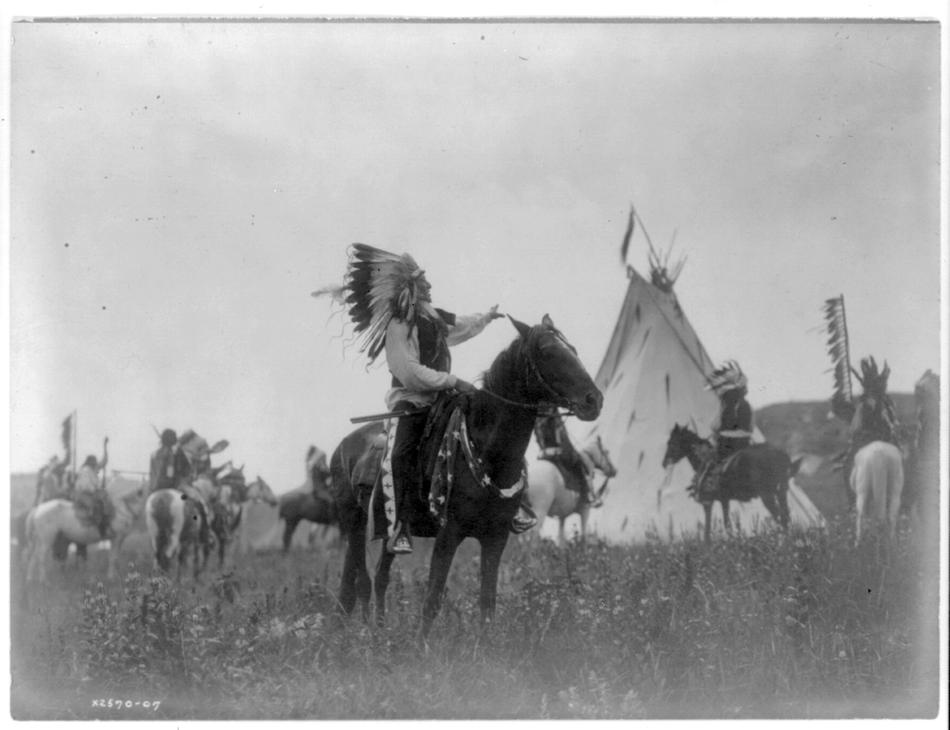

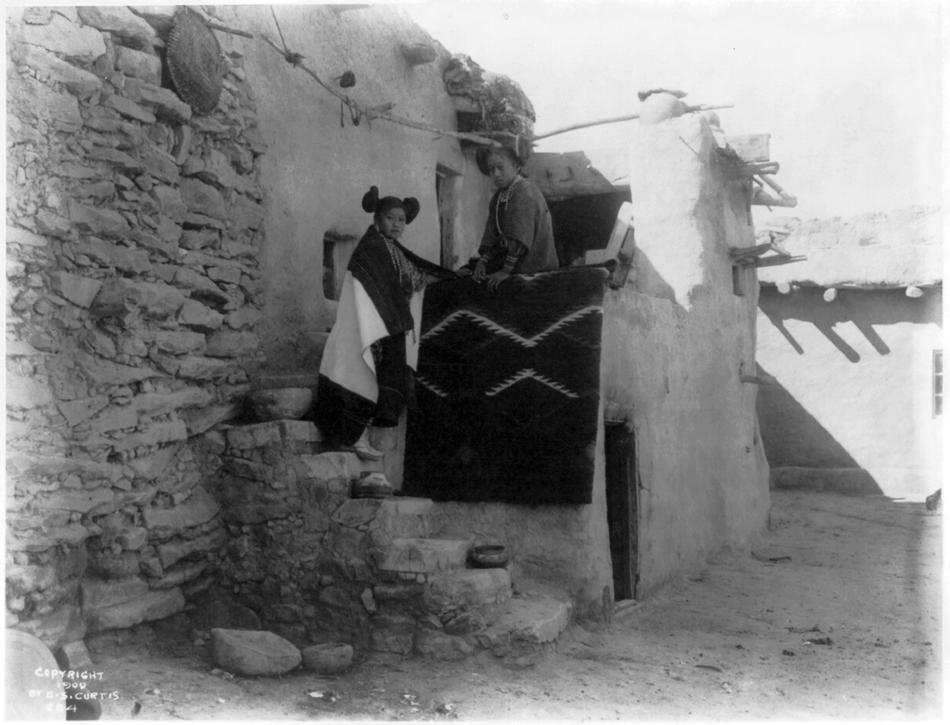

His ambitious project involved photographing more than eighty tribal groups west of the Mississippi–everyone from the Eskimo (Inuit) in the far north to the Hopi and the Comanche in the southwest to the Ute and Cheyenne and a multitude of others in between.

Curtis was born in 1868 near Whitewater, Wisconsin where he lived until he was six years old. HIs father, a Reverend and Civil War veteran, then moved the family to Minnesota.

Around that time more than 200 battles were being fought between US troops and Native American tribes–from the Dakota Territory down to Mexico. When Edward Curtis was eight years old Sioux and Cheyenne warriors defeated General George Custer and his troops at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Curtis went to school until sixth grade then dropped out. Soon after he became interested in photography and built his first camera. The lens for his camera was brought back from the Civil War by his father. He and his father also shared a love of the outdoors and spent time together camping and canoeing. At seventeen, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, then two years later, when his family moved to Seattle, he became a partner in a photo studio.

Curtis went to school until sixth grade then dropped out. Soon after he became interested in photography and built his first camera. The lens for his camera was brought back from the Civil War by his father. He and his father also shared a love of the outdoors and spent time together camping and canoeing. At seventeen, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, then two years later, when his family moved to Seattle, he became a partner in a photo studio.

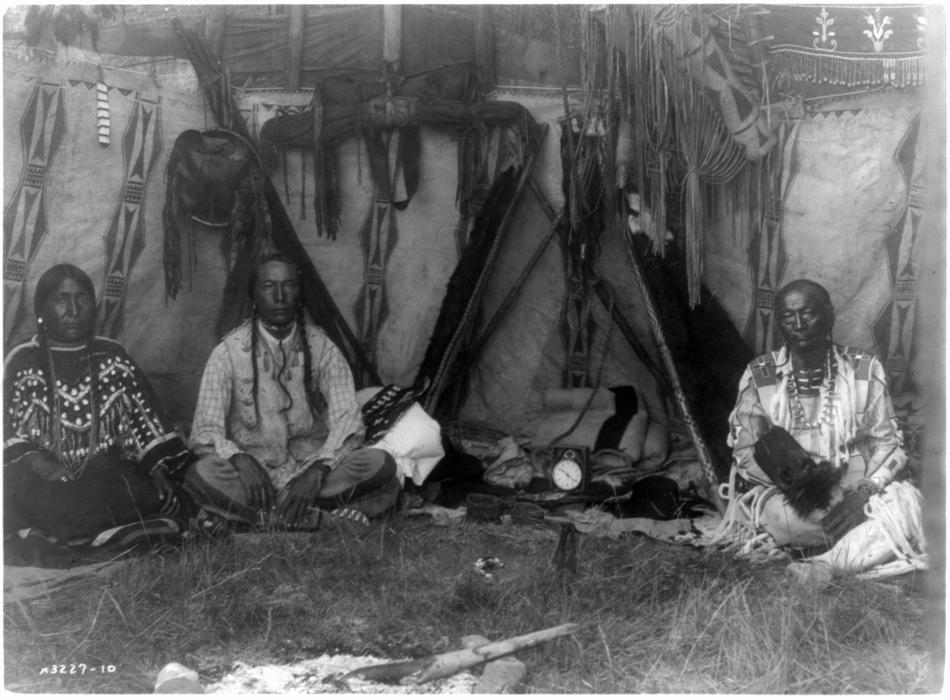

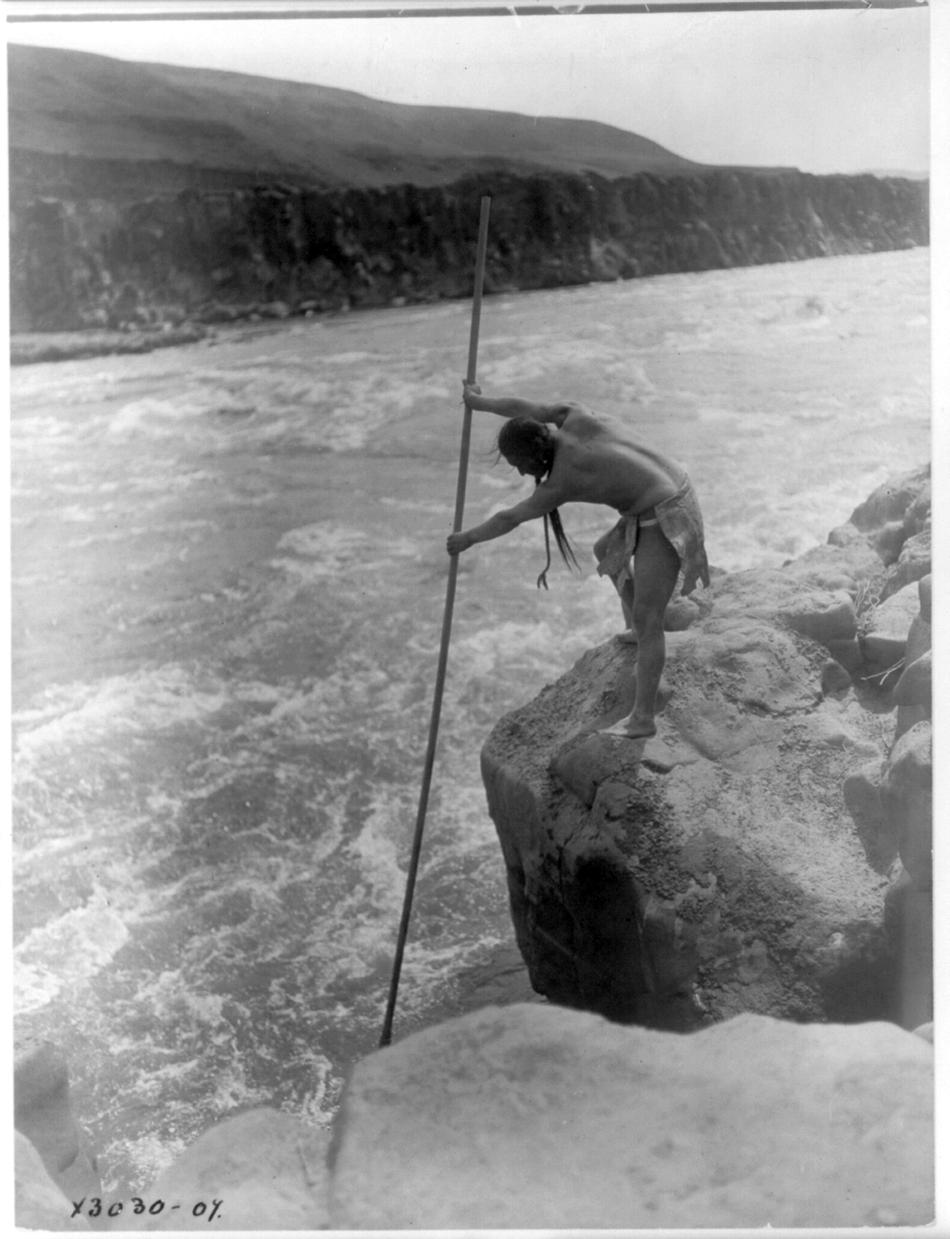

His first Native American portrait, created in 1896, was of Princess Angeline, the elderly daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. It wasn’t long after that he launched into his epic project documenting the Native American traditional way of life–their dress, ceremonies, food, clothing, dwellings, burial customs, manners, and daily life.

Though he struggled to gain funding, eventually J.P. Morgan offered him $75,000, to be paid at $15,000 per year for five years, to create his 20-volume series entitled The North American Indian. It would comprise over two thousand photogravure plates and narrative about America’s indigenous, and Curtis feared, vanishing people. Native Americans were considered “savages” by many at the time, forced from their land and stripped of their rights.

Curtis would later write the following foward to Volume I of The North American Indian.

“The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once….”

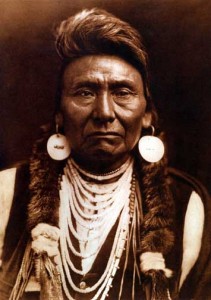

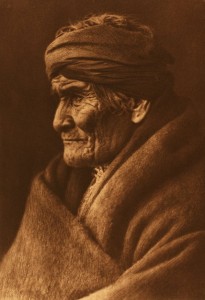

During this ambitious project, Curtis became known by some tribes as the “Shadow Catcher” as he captured the likeness of many important and well-known Indian people of that time, including Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow and others. Not only did he create thousands of images, but he recorded hours of rare ethnographic information, including some 10,000 wax cylinder sound recordings of Indian speech, music, and tribal mythologies.

It took far more than five years to create all twenty volumes, and far more money. Curtis sacrificed much in order to fulfill his dream of documenting America’s indigenous peoples. Not only was he perpetually broke, and continually trying to find financing for the project, but his family life took a beating as well. His wife divorced him after twenty-seven years and his four children grew up essentially with an absent father much of their childhoods.

Curtis’ photographs, while recognized as some of the most important work of its time, have received criticism because they are said to be romanticized versions of Native American culture, and contrived reconstructions rather than true documentation. He was known at times to remove “modern” items from an image to make it more authentic.

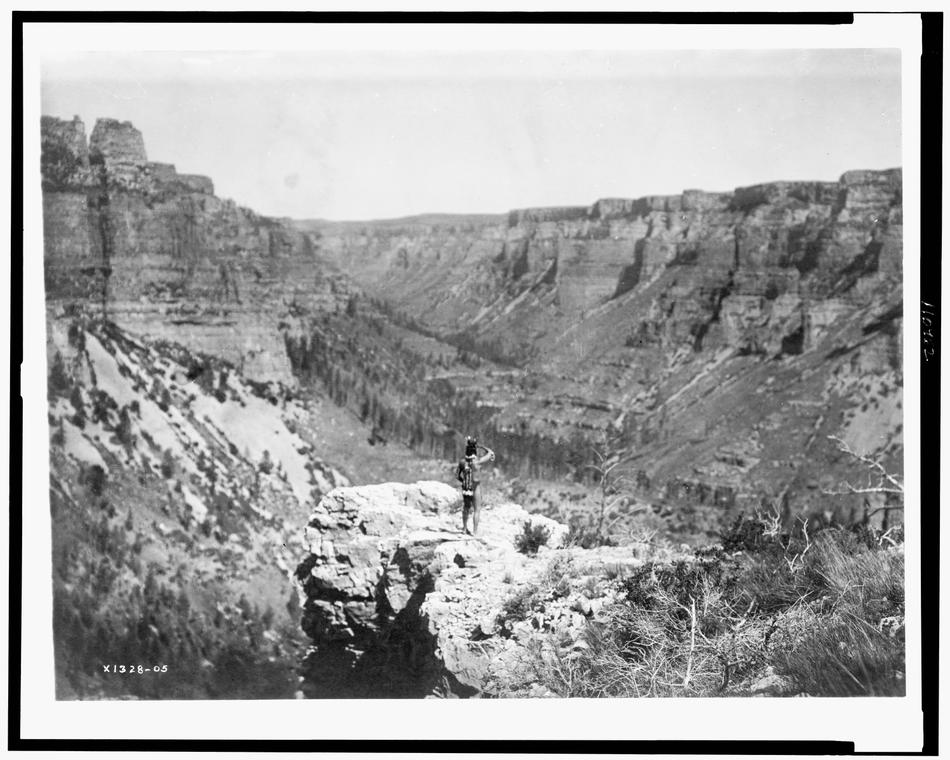

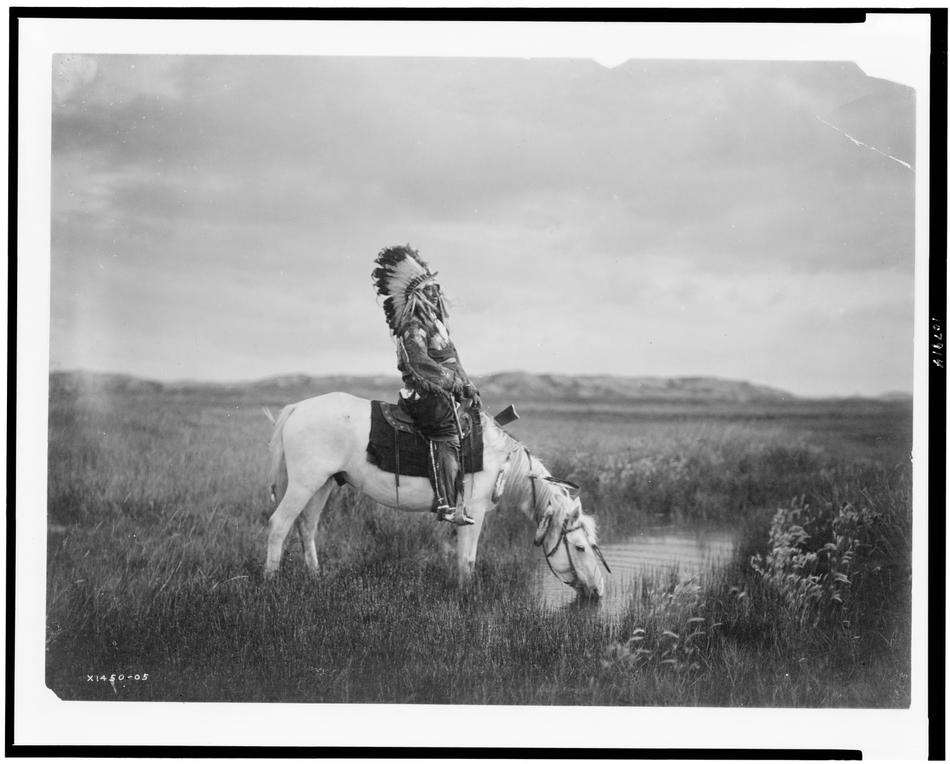

Below are images selected from The Library of Congress’s Edward S. Curtis Collection. Some were published in The North American Indian. Others were not.

After thirty years of devoting his life to this difficult project Curtis had both a physical and nervous breakdown. Even sadder is that after all his work, interest in the American Indian declined and less than 300 sets of The North American Indian were sold. Curtis spent the remaining years of his life with his daughter Beth and her husband in Los Angeles. On October 21, 1952 at the age of 84, Edward Curtis died of a heart attack in Los Angeles, virtually unknown.

When I think of Curtis, I can’t help but marvel at the magnitude of his work and the dedication involved in creating it. The legacy he left behind is a gift, and something future generations will certainly be grateful to have.

Writer, George Horse Capture (great grand-son of Horse Capture of the Blackfeet Indian people), states it perfectly on on PBS’s American Masters website:

“Such a massive project is almost incomprehensible in this day and age. In addition to the constant struggle for financing, Curtis required the cooperation of the weather, vehicles, mechanical equipment, skilled technicians, scholars and researchers and the Indian tribes as well. He dispatched assistants to make tribal visits months in advance. With the proper arrangements Curtis would travel by horseback or horse drawn wagon over paths or primitive “roads” to visit the tribes in their home territory. Once on site Curtis and his assistants would start work by interviewing the people and then photographing them either outside, in a structure, or inside his studio tent with an adjustable skylight. Employing these and other techniques over his lifetime he captured some of the most beautiful images of the Indian people ever recorded.”

To see more of Curtis’ photographs take a quick peek at this Google link: Curtis Images.

This is also a nice slideshow on YouTube with Native American music in the background. And of course Amazon has a slew of books by or about Edward Curtis.

What are your thoughts? Do you think Curtis perpetuated Native American stereotypes by posing some of his images, and/or removing modern items, or do you think he preserved a traditional way of life?

Fascinating man, fascinating piece of history. These photos are epic. I’ve seen many before and am in awe of what it took for Curtis to create these photos, which show respect and humility, honoring his subject in an exceptional way.

Wouldn’t you love to sit down and have a conversation with him? Clearly, he was a unique character to live the life he did and create this body of work. Regardless of his critics, I’m grateful for the legacy he left us.

That hat. Is. AWESOME!

You crack me up, Tracey. Who cares about the photographs. It’s the hat, silly! Thanks for bringing such a big smile to my face today.

Thanks for bringing such a big smile to my face today.

Anyone who pursues passion at the cost of the material comforts of life is a true chronicler. The fact that he removed modern elements from his images was only to reinforce and portray what life was really like before the invasion of foreign people and their cultural artifacts.

Lovely read, Becky!

Well said, Namita. I marvel at Curtis’ dedication, especially in light of the fact he began working in a time before the convenience of modern transportation (Ford’s Model T was just going into production and the first manned helicopter flight was just taking place in 1907). The pure physicality of getting to some of these locations was a feat unto itself. I can only imagine the challenges along the way. To produce this body of work says a lot about the depths of his passion. I’m glad you enjoyed reading about him.